Pendleton, Oregon

Two things have pushed me forward in my quest to make books: 1. Getting myself into situations that were way over my head then having to work my way out of them, and 2. Keeping a vivid sense of the worst-case-scenario close at hand and running like Hell to stay ahead of it.

So when Jim Reid-Cunningham asked if I would make a presentation to the Guild of Book Workers at the 2007 Standards of Excellence Conference, I thought, “Now THERE’S a venue where a flop could effectively end my career...Let’s do it!”

Now, while “book artists” are often regarded as the lower end of the food chain when it comes to traditional fine binders, being given a mandate to be innovative in a field marked by thirty years of rampant innovation is a tall order, and many book artists have risen to the challenge. We can thank PBI, Standards and other presentation venues for encouraging them to jump into the deep end.

I knew that I wanted to create an exposed-spine binding that allowed for a rich, all-over design on the spine – something that amp-ed up existing bindings by sheer volume and density of thread. I experimented with a wide range of options, beginning with a basic stitch that would basically provide a substrate for doing thick embroidery work over the top. As you know, ideas are one thing and the basic laws of physics are another. Each design proved to be either physically impossible or, possible, but rattier looking than a third grade string art project with no structural integrity. I began to panic.

I needed to ditch the embroidery and find inspiration closer to home.

Living in Pendleton, we’re surrounded by amazing fine craft. The rich traditions of both the cowboy and Native American cultures are alive and well in the saddles, silver work, blankets and beadwork that are created here. I find the basket twining and rawhide braiding especially compelling.. My brother-in-law Joey Lavadour, a member of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and of Walla Walla descent, is a master weaver and amazing teacher. Tim George, who works with the legendary Hamley & Co. is a master rawhide braider. Both were endlessly generous in providing encouragement as I tried to adapt each craft to two bookbinding structures, as described in my proposal, “..inspired by the Cowboy and Indian heritage of Eastern Oregon”.

The design process always brings to mind an assignment my friend Mare Blocker uses with her drawing students – “Draw your brain as a carnival ride”. Just about the time I think I’ve got a fabulous idea, riding high on the glee of my own cleverness, the bottom drops out and I realize that I don’t have a clue what I’m doing. I guess it’s that thrill-seeking adrenaline junkie in me that compels me to take the ride over and over again. After so many gut-wrenching cycles over the years, you finally come to trust that you will come out the other side, even though the fear and anxiety are always just as intense.

The basket twining inspired binding seemed like it would be the easiest. 14th century account books that employed weaving over long stitches seemed to be a natural departure point, but I also felt compelled to employ linen cord in some way, as it’s most similar to the hemp cords that Joey weaves his baskets over.

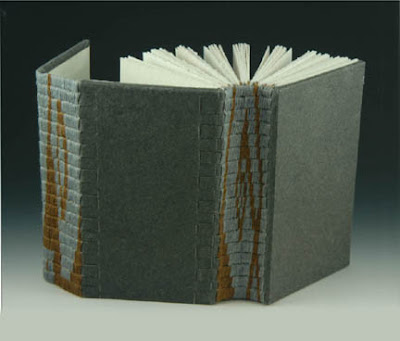

After several miserable attempts at weaving perpendicular to the spine, I finally figured out how to make it work going the other direction. I’m sure I’m not alone in having had my mind wander while executing a packed sewing, imagining how that lovely and orderly linen thread over 12 ply linen cord design would look if replicated to fill the spine and left exposed in the finished book. Throw a little color variation in there and it would be hot.

One night we were watching a Sundance Channel piece on mountain bikes that were made from bamboo. The engineer connected the parts by dousing strands of frayed-out hemp cord with epoxy, forming it around the joints then sanding it to a smooth, beautiful surface. Ah ha! I thought. I would fray out the cords, epoxy them to cover boards and sand them to a gorgeous sheen.

After being sufficiently frightened by the State of California warning on the epoxy label, I conducted a few experiments. The finished surfaces turned out looking much more like dull, grey chipboard rather than the luxurious wood-like sheen I’d envisioned. Never mind the fact that I’d be up in front of 100 conservation-minded experts extolling the virtues of bookbinding with epoxy.

So I nixed that idea and set aside the fluffy sample to concentrate on the “cowboy” binding. On a whim a few years ago I had picked up Bruce Grant’s Encyclopedia of Rawhide and Leather Braiding and had been playing around with teaching myself some basic braids. I'd incorporated some flat braids, covered rings and turk's head knots in a design binding of The Oxbow Incident and liked the textures a lot. I'd started practicing covering some tool handles in the studio with braided leather and was captivated by the technique, which allows the weaving to appear to emerge from the butt of the handle as if by magic. In my head, this concept could be adapted to a binding.

Knowing that I didn’t want to demonstrate leather or vellum in front of GBW members who were true experts with those materials, I tried to find a suitable substitute. Pergamenata Parchment seemed like a good idea, but, it wasn’t strong enough unless lined with Tyvek and cracked when folded against the grain. The translucency and strong pull was also a problem when covering boards.

I had hauled some pieces of Tim Barrett’s papercase paper back from a book arts gathering years before and started experimenting with those. The paper was perfect. The book structure, however, was problematic. I was working with models where two boards were covered separately with strips extending from the spine edge that were then to be interlaced and woven back over the spine sewing and covers. I was able to create just one miniature model that held promise, but when I tried to weave the strips on a larger scale, the materials seemed to stage a rebellion against my best laid plans. At this point it was just 8 weeks before Standards and I was faced with two dead-end projects.

Then, just as in the old Reese's commercials where her peanut butter gets in his chocolate and vice versa, the two ideas intersected, and weaving over the extended paper supports instead of linen cord seemed to hold promise.

The first model I made actually looked pretty good. Now I had to get busy creating more samples to show off different variations on that model. Weaving is time consuming, and I worked day and night. I finished a fifth book on the flight to Dallas and another two, one full-size and one miniature, in my Standards dorm room.

The good news is, the presentation seemed to go fairly well. I don’t think it totally rocked the world of the Guild members, but most attendees seemed reasonably engaged and intrigued.

The culmination of my week was when one of the respected Guild big wigs confided in me that, “..sometimes the ‘book arts’ things can be a bit flakey, but your wasn’t flakey at all”. What more can you ask for, really?

Now, being able to make a book for yourself is one thing. Trying to explain its construction to others is something else altogether. Communicating the steps of a fairly complex and unfamiliar binding was, and continues to be, a challenge. After sending a set of instructions with images to Peter Verheyen for possible inclusion in The Bonefolder, I woke up with a start one morning, realizing that there was a much easier way to streamline the addition of the gatherings. Those instructions were updated just yesterday, and I’m sure that more refinements will develop in the future.

My next goal is to create at least 50 twined bindings and get them placed in teaching collections across the country. In the same way some people knit, this stitch has become something that I can practically do without looking, and I find it very relaxing. I’ve been experimenting with some of Bridget O’Malley’s heavy papers, heavy vellum (the real stuff from Jesse Meyer) and recycled materials like shipping straps, all with good success.

The culmination of this project would be to see others take on this binding, creating their own designs and variations. That would make the scary parts of the roller coaster ride all worthwhile.

4 comments:

Wow! Not flaky at all. These bindings look like they would be very satisfying to make and wonderful to hold in your hand. Thank you for including such a lot of pictures.

~Sophia

Very, Very, Very interesting! I think the books are so beautiful! I enjoyed the humor in the presentation dialog. There was also such an openness about the process and what worked and what didn't. It was like an adventure you were asked to go on at the last minute and didn't know what it would be like, but were pleasantly surprised! Thanks, +Sue+

Fantastic! I was searching for creative book coverings for my report project and now I have a great inspiration. Thank you for you openess to share.

Thanks for sharing! I've been been there, inventing new bindings, and I liked the bit about your ideas and the laws of physics not lining up.

Post a Comment